An examination of the assertion that the later author writes like his predecessor.

SIMENON SIMENON. GARNIER ET SIMENON: DES OISEAUX DE MEME PLUMAGE ?

Un examen de l’affirmation selon laquelle Garnier écrit comme son prédécesseur.

SIMENON SIMENON. GARNIER E SIMENON: DUE PICCOLI DELLA STESSA COVATA?

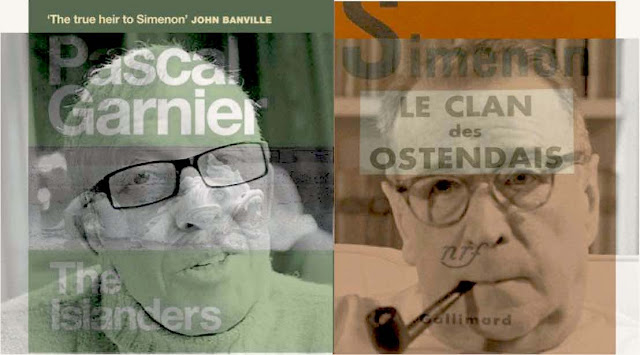

Pascal Garnier (1949-2010) and Georges Simenon (1903-1989) draw comparison of their writing. Jose Ignacio of A Crime is Afoot

put me onto Pascal Garnier when he blogged: “The prize-winning author

of more than sixty books, he remains a leading figure in contemporary

French literature in the tradition of Georges Simenon.” John Banville called Garnier “the true heir to Simenon,” and Brian Greene

affirmed “Simenon is the writer who gets name-checked the most when

people critique Garnier’s novels and search for comparisons.” Such comments stimulated me to assess

how closely this children’s book writer who gravitated to noir fiction

matches up with the more prolific and renowned Simenon.

Of 63 publications in total, none of Garnier’s noir books appeared until 7 years after Simenon had died. Of the 17 French originals published from 1996 to 2012, a total of 9 English translations have appeared from 2012 to 2016. I picked three from the French as a hopefully representative sampling for this comparison project. Frankly, I feared they would turn out to be Simenon knockoffs, and as the résumés below suggest, they do exude a roman dur mood.

In The Front Seat Passenger/La Place du mort, Fabien’s wife and her lover die side by side in a car accident. Stunned but vengeful, Fabien tracks down his previously unknown rival’s widow determined to seduce the wife of the man who had seduced his, triggering an irrepressible chain reaction.

In The Islanders/Les Insulaires, Olivier

returns to his hometown to bury his mother and reconnects with his

former girlfriend. They join her blind brother and a homeless man for

dinner and everything spirals into a crazy nightmare.

In Too Close to the Edge/Trop près du bord, elderly widow Eliette takes in a low-level hood because she feels isolated and bored. When seemingly out of the blue his daughter appears and a neighbor dies, things spin out of control.

All three stories start out much like the romans durs, but not at all like the Maigrets. These short (144, 144 & 200 pages) works feature prose à la Simenon: straightforward and strong, tight and terse, in atmosphere, description, and dialogue. As well, the characters present as pretty ordinary people, none of them truly happy in their dreary existence. However, the stories diverge dramatically from Simenon’s style by being humorous as well as black. (I don’t recall ever smiling, let alone laughing, when reading his romans durs.) What is more, the Garnier stories differ in their clever growing tension and stronger pull to find out exactly what is going to happen. In contrast, Simenon’s denouements tend to be predictable; one senses in advance what’s likely to take place. In fact, the Garnier stories are more thriller and horror than mystery. Stephen King comes to mind as perhaps a better comparison (Misery being one example).

At least for me, the bottom line is that, despite some Simenonien similarities, Garnier stands as his own man.

David P Simmons