On the incarceration theme in a “roman dur” recently translated, “The Mahé Circle”

SIMENON SIMENON. L’HISTOIRE D’UN PRISONNIER DANS LES GRIFFES DE SA FAMILLE

Sur le thème de l’incarcération dans un “roman dur” récemment traduit, Le Cercle des Mahé

SIMENON SIMENON. LA STORIA DI UN PRIGIONIERO NELLE GRINFIE DELLA PROPRIA FAMIGLIA

Sul tema della carcerazione in un "romans dur" recentemente tradotto Le Cercle des Mahé

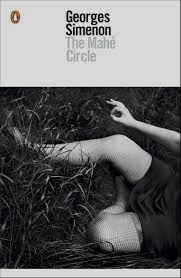

In The Mahé Circle, Simenon cleverly blends two themes by moving the novel’s action back and forth between the French mainland and a Mediterranean island. Gradually, over the course of a few years, the protagonist recognizes his life of restraint and transitions into one of reaction. Doctor François Mahé is a general practitioner living in Sainte-Hilaire with his wife and two young children. A routine island vacation exposes the 32-year-old man to a unique existence unlike his mainland existence and the story evolves step by step to end on the island.

Back home again, François contemplates his lifelong setting: it “resembled a post card” in which “he saw and felt himself embedded in a world of frightening immutability.” Surrounded by “15 or 20 Mahé-labeled houses” in a countryside “filled with Mahés,” François recognizes ”what was strange, troubling, and even agonizing” was the same “immutability” within his household where he is trapped by two women of whom “one would have said they had been knitting forever.” So, he begins to think that “he has to make an effort to escape this depressing feeling.”

In point of fact, his mother is the chief problem. Widowed when François was only three, she raised him, made him a monsieur, bought his house, made him a doctor, and acquired a practice for him. Most importantly, “she was the one who got him married,” and he kept on living with his mother because “when he got married, he had not had, like others who left their homes, a sensation of liberty.” Now, he realizes “it was not for him that his mother had chosen her—he was thinking about Hélène, of course—it was for herself.” For a long time, he had felt he could not have asked for more: peace and leisure. Fishing and hunting. Good dogs and a wife who “helped his mother care for him […] because the rule is to care for the man, the one who makes the living for the household.” As his eyes open wider, he sees how these two women “had imprisoned him and he, the big naïve one, had not noticed it.” Despite her “gentle and soft” demeanor, “he had lived too much with his mother to be able to say squarely: “We will do this or that…” In sum, “she was the only one he was afraid of” and “he always had the same fear of her.”

During four trips to the island with his family—but without his mother—François senses the potential for another life unlike the lifetime confinement in Sainte-Hilaire, which becomes ”another world” in which “everything had ceased to live its normal life.” In comparing the two locations, what titillates his imagination above all, is “the red spot,” this being Elisabeth, a mysterious little girl who “must not own any other dress than the red cotton one,” who captivates him. Ultimately, among the many symbolic images “engraved in his memory with strong force,” it is “the red dress above all” that haunts and possesses him. Over time, as the “skinny” girl develops breasts and a “womanly look,” François’ attraction becomes sensual as well as spiritual. Despite his obsessive attraction to “the red spot,” he just observes her and does not speak to her, inexplicably remaining “enormous” in “his stupid immobility.” Still, Simenon’s narrative seems to promise he will act in time.

David P Simmons

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento

LASCIATE QUI I VOSTRI COMMENTI, LE VOSTRE IMPRESSIONI LE PRECISAZIONI ANCHE LE CRITICHE E I VOSTRI CONTRIBUTI.